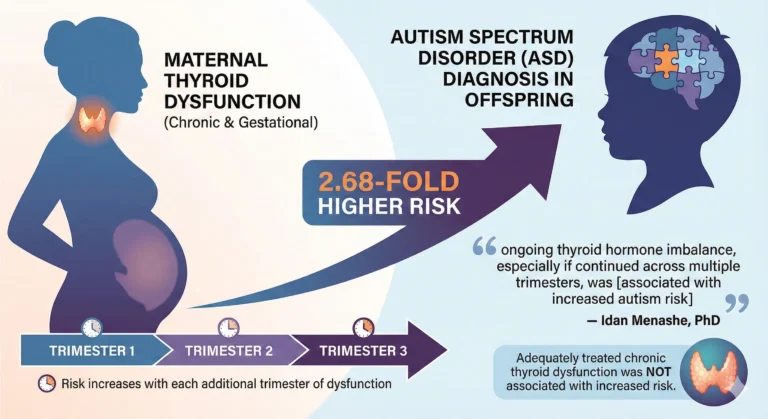

Key findings from the study indicate that women who experienced thyroid dysfunction both before conception and during pregnancy had a 2.68-times greater likelihood of having a child later diagnosed with autism, and that the risk increased with each additional trimester affected by thyroid imbalance.

According to research published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, maternal thyroid issues that occur before or persist throughout pregnancy may heighten the probability of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in their children.

Idan Menashe, PhD — who leads the department of epidemiology, biostatistics and community health sciences at the faculty of health sciences at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev — explained the results stating:

“The findings of our study suggest that while adequately treated chronic thyroid dysfunction was not associated with increased autism risk in offspring, ongoing thyroid hormone imbalance, especially if continued across multiple trimesters, was.”

Study Details

Menashe and his team performed a retrospective cohort analysis involving women who delivered a single baby at Soroka University Medical Center in Israel between 2011 and 2017. Chronic thyroid dysfunction was determined using ICD-9 diagnostic codes for hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism in patient health records. In contrast, gestational thyroid dysfunction was identified through thyroid hormone testing during each trimester of pregnancy.

Of the 51,296 women included, 8.6% had some form of thyroid dysfunction. The breakdown was as follows:

– 1,161 had chronic hypothyroidism

– 1,600 had gestational hypothyroidism

– 1,054 had both chronic and gestational hypothyroidism

– 100 had chronic hyperthyroidism

– 376 had gestational hyperthyroidism

– 15 had both chronic and gestational hyperthyroidism

Children were diagnosed with ASD at a median age of 4.6 years. When comparing all women with any thyroid disorder to women with normal thyroid levels, there was no overall difference in ASD incidence.

However, women with both chronic and gestational thyroid dysfunction had a significantly higher risk of having a child diagnosed with ASD compared with women who were euthyroid (adjusted HR = 2.68; 95% CI, 1.52–4.72). A similar increased risk was found specifically for women with both chronic and gestational hypothyroidism (aHR = 2.61; 95% CI, 1.44–4.74).

When thyroid dysfunction occurred during pregnancy only, risk rose with the number of trimesters affected. Each additional trimester of thyroid imbalance was linked to higher ASD risk for:

– gestational hypothyroidism alone (aHR = 1.39; 95% CI, 1.16–1.68)

– both chronic and gestational hypothyroidism (aHR = 1.28; 95% CI, 1.02–1.93)

The highest autism risk was observed among women who had gestational hypothyroidism during all three trimesters. Menashe noted that the connection between prolonged thyroid abnormalities during pregnancy and elevated ASD risk in children was unexpected.

He emphasized:

“Our findings underscore the need for routine monitoring and timely adjustment of therapy to maintain normal thyroid hormone levels throughout pregnancy.”

Menashe also noted that more research is required to understand the mechanisms through which abnormal thyroid hormone levels influence fetal brain development.

For further correspondence, Menashe can be contacted at idanmen@bgu.ac.il.

This research contributes to an expanding collection of epidemiological studies (such as Kaplan ZB et al., Thyroid, 2024) that imply a link between maternal hypothyroidism during pregnancy and an increased likelihood of ASD in children. In this Israeli retrospective cohort, the offspring of women who were hypothyroid both before and during pregnancy showed more than double the risk of receiving an ASD diagnosis compared with children of mothers with normal thyroid function. Importantly, hypothyroidism occurring only before pregnancy or only during pregnancy did not demonstrate a similar association, indicating that the duration and continuity of untreated hypothyroidism may be key contributors.

The study’s strengths included multiple thyroid function assessments throughout pregnancy and a long follow-up period. However, its retrospective nature introduced several limitations. The researchers did not evaluate variables such as maternal iodine levels, socioeconomic status, or thyroid autoimmunity, and they also lacked data on levothyroxine treatment. Additionally, the study did not examine outcomes related to isolated maternal hypothyroxinemia. The small number of ASD cases among children of mothers with hyperthyroidism limited meaningful analysis in that subgroup. Existing knowledge already highlights the importance of properly treating overt hyperthyroidism during pregnancy to ensure healthy obstetric and developmental outcomes.

While this study raises the possibility that even subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy may elevate ASD risk, the ability of levothyroxine therapy to reduce this risk has not yet been tested in clinical trials.

This perspective was provided by Elizabeth N. Pearce, MD, MSc, of the Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, who reported no relevant financial disclosures.